Preventing and Addressing Inequalities in Cancer Care: An Interview with Toral Shah.

(12 Minute Read)

Picture this:

You are at your first appointment after your cancer diagnosis, when you meet your oncologist. They begin to explain what treatment you’ll need, why you’ll need it, and what precautions you might need to take during treatment. However, you soon realise that 20 minutes have gone past and you are even more confused now then you were at the beginning.

What do you do? Do you ask a question? What is the response?

The oncologist then calls another colleague in to discuss your care.

Are you involved in the conversation they’re having, or do they talk about you as if you aren’t there?

As the below discussion shows, the answers to these questions may have a lot to do with your ethnicity – specifically, the colour of your skin.

In the UK, our healthcare system is free at the point of access to every citizen. However, what happens after this point – and how long it takes to get there – depend largely on a series of factors that are outside of our control, such as class, postcode, and ethnicity.

Whilst the impact of these factors on people’s health and wellbeing needs to be addressed at the governmental and institutional level, there are many things that people can do to help themselves.

Here, we talk to nutritional scientist and functional medicine practitioner Toral Shah about health inequalities in cancer care due to systemic racism, the need for inclusive awareness campaigns, and the power of nutrition and self-advocacy. As a two-time breast cancer survivor, Toral is passionate about reducing the number of people who lose their lives to cancer every year. Her work in nutrition and functional/ lifestyle medicine lives through her brand

The Urban Kitchen , through which she provides one-to-one consultations, consultancy for brands, and delicious, healthy recipes. Nutrition is a major element of cancer prevention, and Toral’s work goes to show how tasty, easy, and colourful it can be to eat for your health!

NatiaCares: Hi Toral! So, you recently gave a talk on health inequalities, and your Instagram posts include some really insightful discussions about racism in health and wellbeing. Was there a particular event that made you so passionate about this topic?

Toral: I’ve been really passionate about health inequalities – particularly in black and brown people – since 2008. I became aware once I was over treatment and getting more involved in breast cancer fundraising that BAME (Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic) groups have poorer outcomes. I’ve been saying this to cancer charities since 2009, but no one’s really been listening until now! With the Black Lives Matter movement and COVID pandemic, these inequalities became much more apparent. This situation gave me the opportunity to really start talking about health inequalities in a bigger context, particularly with cancer, and how health inequalities aren’t just due to socio-economic position and education or genetics. A lot of them are based on structural and institutional racism – one of the backbones of how our country is set up. Black Lives Matter meant more people were listening, which meant that what I had to say about health inequalities started to be heard. But even within this context, we still have a long way to go before the necessary changes are made.

NatiaCares: What’s the situation for people here in Britain who aren’t white, when it comes to cancer treatment and care, and why do you think this is?

Toral: So, in the UK currently, 13% of the population describe themselves as being a member of the BAME (black, Asian, and ethnic minority) community. This is projected to rise to 20% by 2026, meaning there will be more people who are not white in the UK. The

likelihood of getting cancer varies significantly throughout this group, but we know that the risk for black men is comparable to that of white men.

However, there are big inequalities throughout various stages of the cancer experience:

Awareness:

Members of the BAME community have less awareness about the signs and symptoms of certain types of cancer than the rest of the population, on average. For instance, South Asian and black women have

much lower breast cancer awareness than white women, yet, of those people who have breast cancer in the UK,

black women are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with advanced breast cancer than white women! Early detection is absolutely key in preventing secondary breast cancer - the earlier you’re diagnosed, the more likely you are to have a better outcome. So, you can see how health outcome and awareness inequalities are connected. Additionally, more black women develop triple negative breast cancer (breast cancer that’s oestrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptor negative) than white women.

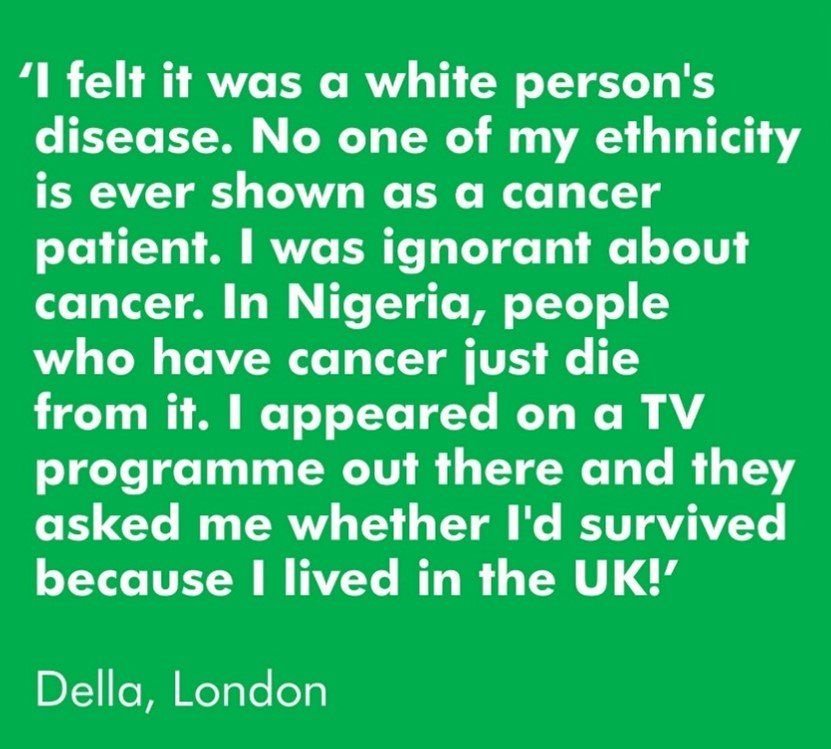

There are lots of different barriers as to why people don’t know more about cancer. Not knowing about the signs and symptoms of cancer may be because of stigma attached to the disease, which causes people not to talk about these things in their communities or families. Awareness campaigns – whether by charities, public health organisations or healthcare institutions – often don’t feature south Asian and Black people. For us to change our behaviour, we need to see what we’d like to change, and how we’d like to behave. If black and Asian people don’t see campaigns that feature them, then they may not feel like it’s applicable to them.

We also know that that the lower the socioeconomic group a person belongs to, and the more poverty there is, the less likely people are to be aware of cancer symptoms , and this will affect their outcome in the long term. Sadly, many people in lower socioeconomic groups are from BAME groups.

Screening and diagnosis:

There is a lower uptake of the NHS breast cancer screening programme among black women in the UK, and uptake of screening generally is much lower in BAME groups than people from the white population. This has serious implications for health outcomes on its own, but black women also have to go to their GP at twice as many times as white women to get a cancer diagnosis. In fact, a Macmillan report has shown that 15.8% fewer black patients than white patients felt they were seen as soon as necessary by their GP before going to hospital in 2017.

Treatment and care:

There are some really disturbing statistics regarding treatment and care of BAME patients with cancer from the same survey. 13.9% fewer patients of mixed ethnic background felt that their test results were explained to them in a way they understood. That means that many people from BAME backgrounds felt that they didn’t really understand what was happening to them and didn’t understand the results of the tests that were done. Imagine how upsetting and stressful that must be! We know that stress can impact our overall health in many ways.

16.6% fewer Asian patients than white patients felt positive about the length of time they had to wait for their test, and, when in the hospital, 11.4% fewer Asian patients said they could find someone in the hospital to discuss their worries and fears.

Patients from mixed ethnic backgrounds were much more likely than white patients to report that staff were talking about them, not too them, during their cancer experience (42.1% and 19.2% respectively). Also, during treatment, people with cancer who are black or Asian are 41 – 48% more likely than those who are white to say they were only partially involved in decisions about their care and treatment.

Finally, we must consider clinical trials, which are often lifesaving or life-prolonging for cancer patients. We know that people who participate in these have better outcomes than the rest of the population, but people from BAME groups are less likely to be invited to participate, and less likely to accept. Barriers to participation may include cultural stigma, fear, lack of knowledge about medical trials, and a very real mistrust of the medical system.

When it comes to different experiences in the hospital, we need to ask why this happens. Is this due to language barriers, cultural or religious issues or due to the unconscious bias of health care professionals who may assume that certain groups of people won’t understand, so their cancer isn’t explained? Bias is hardwired in our brains; when we were hunter-gatherers, we needed to know who we could trust quickly to protect ourselves. Our brains understood those who looked most similar to us as being most trustworthy, so this is how we relate to people of our own ethnicity. Whilst we all need to examine our own bias and privilege, it is even more important for healthcare professionals to do so as this affects BAME groups health outcomes.

Support, mental health, and end-of-life care:

Having cancer takes a real toll on all aspects of your life, but there’s a distinct lack of physical, mental and emotional support for BAME people.

For instance, support items such as lymphoedema sleeves and wigs often are not provided for women of colour. Although lymphedema sleeves now come in colours other than light pink-beige, this was not the case for a long time and they still are not provided in some areas in the UK. There are so many women, particularly black women, who have been offered wigs that are for white women.

BAME people are less likely to attend cancer support groups, possibly because they don’t know about them, don’t feel welcome, or there aren’t any that cater for their needs. It’s wonderful to see is that there are more and more dedicated groups appearing for particular demographics. For instance, Leanne Pero started Black Women Rising, which is a phenomenal organisation supporting black women with breast cancer. There are also lots of Asian cancer support groups, but these are all organisations started by the communities and patients themselves, rather than charities or health organisations.

People from certain cultures are also unlikely to talk about their emotional and mental needs with GPs and other doctors, and, similarly, may feel unable to discuss cancer, treatment and diagnosis with others in their communities because of cultural stigma. Education, and creating appropriately trained staff in charities and health organisations who understand the cultural, religious, and other issues is key to changing this.

There is also a lower uptake of palliative care amongst people from BAME groups than white people. There are several reasons for this, including a lack of referrals, a lack of knowledge, hospices being located outside of cities, and varying cultural perceptions around death and dying.

NatiaCares: How else do these issues need to be dealt with?

Toral: It’s clear that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to cancer care and treatment, and this needs to be reflected in policy and action from cancer institutions. Information needs to be disseminated in different ways to ensure that different groups are reached. This may include creating awareness campaigns that feature a diverse range of people, adverts in different publications serving different communities, information in different languages, and anti-racism and diversity training within charities and health organisations

We also need to be paying specific attention to how we can increase the uptake of various resources. For instance, I’m working with a brand called Ancora to find out how we can diversify clinical trials, because it makes such a difference to outcomes. It’s clear is that we need to personalise care and not group patients. As healthcare professionals, we need to be aware of both our unconscious bias and the cultural factors that can create these inequalities.

NatiaCares: So, what can people do for themselves and those around them?

Toral: The first thing is being aware of the signs and symptoms of cancer. This isn’t just personal – people need to make sure that they remind their friends and family to know what to look out for, to keep checking, and to go to the doctors for screening or if something doesn’t seem right. We all have a responsibility to have these conversations and look out for each other.

Then, there is being aware of risk reduction behaviours. Good nutrition, regular moderate or vigorous exercise, not drinking alcohol and not smoking are all very important ways that people can change their lifestyles to reduce their risk of getting cancer.

For people who do get ill, support groups – whether online or in people’s local communities – are something that more people should be aware of and able to access. There’s a wealth of these groups on social media (Instagram or Facebook) for people from every demographic and with any type of cancer, and it’s often worth checking online to see what’s available in your local area. For those who don’t see the right group for them, it’s always worth considering starting one!

Holistic interventions such as meditation and yoga through programmes like the ones available on the NatiaCares app are also proven to help people cope with some of the effects of cancer and its treatment. With the COVID-19 pandemic, many support organisations such as Penny Brohn and Breast Cancer Now have taken their services fully online.

Finally, people should educate themselves and others about various self-advocacy techniques, such as asking questions and making notes during appointments, keeping a journal, and doing some pre-appointment research. Using these techniques can help people to have more input in decisions about their care and treatment. There are some new apps to help with this including Vine Health and Owise.

Thank you Toral!

Toral and NatiaCares will soon be working together again to discuss some of the risk reduction and self-care behaviours detailed above. Watch this space!

And, as always, thanks for reading.